The Holocaust in Bulgaria is the persecution and extermination of Jews in Bulgaria and in the territories annexed to it during the Second World War as part of the Nazi policy of “the final solution of the Jewish question.” Despite the fact that Bulgaria was an ally of Germany in the war, almost the entire Jewish population was saved. The Israeli Yad Vashem awarded 20 Bulgarians with the honorary title “Righteous Among the Nations” for the salvation of Jews during the Holocaust.

The salvation of the Bulgarian Jews is an episode in the history of Bulgaria during the Second World War, when, from 1943 to 1945, about 50 thousand Bulgarian Jews were saved from extermination by the Righteous Among the Nations and those who were not indifferent. Among the initiators of the salvation of the Jews were Dimitar Peshev, Exarch Stefan of Bulgaria and Metropolitan Kiril of Plovdiv. They persuaded Tsar Boris III to stop the extradition of Bulgarian Jews to the camps. The ban on the deportation of Jews came into force on March 10, 1943. The act of the Bulgarian authorities is widely revered in the world, and Israeli President Shimon Peres expressed special gratitude.

Bulgaria was an ally of Germany in the Axis bloc, and formally Boris III was forced to fulfil all the requirements of Adolf Hitler in order to receive further assistance and support from Germany. In Bulgaria, in the 1930s and 1940s, radical and anti-Semitic sentiments intensified, and supporters of radical parties occupied a significant proportion of the posts in the Bulgarian government. One of them, Prime Minister Bogdan Filov, on October 8, 1940, signed the “Law on the Defence of the Nation”, which limited the rights of Jews, and the Minister of the Interior Alexander Belev was involved in the deportation of 11 thousand Jews from the occupied Greek Thrace and Vardar Macedonia to Treblinka. On February 22, 1943, Belev concluded a secret agreement with SS representative Theodor Dannecker on the deportation of Jews from these regions “to settle in the region of East Germany”, which would be carried out directly by Germany. On the night of March 3-4, 1943, the Jews of Greek Thrace, Eastern Macedonia and Serbian Pirot were taken by train to Lom across the Danube, then sent along the Danube to Vienna, and from there sent to Treblinka. On March 15, almost all of them were executed: only about a dozen escaped death.

Even though there were strong anti-Semitic sentiments in Bulgaria, the position of the Jews in the country was fairly stable and secure. On the eve of World War II, about 50,000 Jews lived in Bulgaria. The establishment of an alliance with Germany and the introduction of anti-Semitic legislation took place. In 1940, the government of Bogdan Filov introduced anti-Jewish legislation similar to the German one. On January 23, 1941, the “Law for the protection of the nation” came into force, which prohibited Jews from voting, running for prime minister, serving in the government, serving in the army, marrying or living in a civil marriage with ethnic Bulgarians, being owners of agricultural land, etc. Limited quotas were set for Jews in universities. This anti-Semitic law was protested not only by local Jewish leaders, but also by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, the Bulgarian MPs and Bulgarian cultural figures.

On March 1, 1941, a protocol was signed on Bulgaria’s accession to the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Pact.

In July 1941, the “Law on a one-time tax on the property of persons of Jewish origin” was adopted, according to which persons of Jewish origin living on the territory of Bulgaria had to pay an additional property tax. As part of the restrictions imposed on Jews in terms of property ownership, the nationalisation and sale of Jewish property began. The money from the sale went to the Bulgarian People’s Bank and by March 1943 amounted to 307 million leva. Auctions for the sale of Jewish property were accompanied by massive corruption and outright theft by government officials. A one-time tax on Jewish property was set at 20% (25% on property over 3 million leva), the amount of fees was 1.4 billion leva – about a fifth of all taxes of that time.

In August 1942, a Commissariat for Jewish Affairs (Commissariat for Jewish Questions) headed by Colonel Alexander Belev was created under the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Bulgaria. In January 1943, an SS representative, Adolf Eichmann’s deputy, Theodor Dannecker, arrived in Sofia with the task of organizing the deportation of Jews to death camps in Poland. On February 22 or 23, Dannecker signed an agreement with Belev on the deportation of 20,000 Jews from Vardar Macedonia and Thrace. Later, Belev crossed out the clarification on Vardar Macedonia and Thrace, and thus the threat of deportation hung over the entire Jewish community in Bulgaria.

The law proposed by Belev for the “defence of the nation”, adopted by the National Assembly in January 1941, served as a pretext for the escalation of anti-Jewish policy. Since November of 1941, mass arrests of Jews marked the preparation for their deportation, in response to which religious and cultural figures flooded the Bulgarian government with open letters and protest statements. After long disputes, Boris III was forced to cancel the decision to deport the Jews.

The initiators of the salvation of the Jews were Dimitar Peshev who presented a letter with the signatures of 43 Bulgarian MPs, and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.

Many Bulgarian politicians initially supported anti-Jewish laws. Peshev advocated the preservation of laws, but at the same time opposed the deportation of Jews to Germany. The Bulgarian government did not provide protection to Jews in the temporarily occupied territories, so no one spoke out against Belev’s actions to expel Jews from Vardar Macedonia and Thrace to Treblinka until it became known that Belev decided to send 20 thousand native Bulgarian Jews to Germany. Nevertheless, protests across the country involving ordinary citizens who blocked the “Holocaust trains” by lying on the rails forced Boris III to stop the deportations. Adolf Eichmann and Adolf Hitler received an official response from Boris III that Bulgaria needed Jewish workers for the construction of railways and other infrastructure: Boris III did officially include Jews in special construction teams.

The decision to deport the Bulgarian Jews caused a massive protest. Demonstrations were held in the capital in defence of the Jews – the Orthodox Church, the intelligentsia, political parties and MPs of the People’s Assembly spoke out against it. Peshev decided to take advantage of the initial success in thwarting the government’s deportation plans and wrote a letter of protest, which he sent to the Speaker of the National Assembly Hristo Kalfov with the signatures of 42 other deputies. In the letter, Peshev denounced the government’s anti-Jewish policy and demanded that it be changed. The position of Deputy Parliament Speaker Dimitar Peshev played a big role. Peshev, having received a message about the impending action, began to gather like-minded people in parliament and presented the Minister of the Interior Gabrovsky with an ultimatum about a public scandal if the action was carried out secretly. As a result, the secret operation planned for the evening of March 23 was suspended. Bulgarian Prime Minister Bogdan Filov wrote in his diary: “His Majesty has completely cancelled the measures taken against the Jews“.

Thus, the initial attempt to deport the Jews from the borders of Bulgaria was thwarted, Daneker and Belev did not abandon the idea of deporting the entire Bulgarian Jewish community, and Eichmann continued to insist on the importance of deportation. Attempts to resume deportations were unsuccessful until the end of the war.

Tsar Boris III stood up for the Bulgarian Jews and told the German leadership that his Jews had to work on public buildings and therefore could not deport them. Germany’s foreign minister, Ribbentrop, put strong pressure on the king, but Boris III was adamant in his defence of the Jews. In a meeting with Hitler and Ribbentrop in March 1943, Tsar Boris succeeded in convincing them that conditions in Bulgaria were different and that the same measures should not be taken against Jews as in Germany. Ribbentrop informed the German Minister Plenipotentiary in Sofia, Adolf Beckerle, of Boris’s opinion in Directive 422 of 4 April 1943. It is clear from Ribbentrop’s telegram that Tsar Boris advocated for Jews from the old borders of the country with pragmatic arguments. The king ordered the Jews to be included in road construction working groups in order to avoid their deportation to Poland. Tsar Boris III issued an order to Interior Minister Petar Gabrovski halting the planned deportation of Jews.

The People’s Court, organised after the coup of September 9, 1944, convicted 39 of the 43 deputies who supported Peshev’s protest letter against the deportation. Of the 39, 20 were sentenced to death, 6 to life imprisonment, 8 (including Peshev) to 15 years in prison, 4 to 5 years in prison, and one to 1 year in prison. There are three acquitted and one dies while awaiting sentencing. Among those executed were Dimitar Ikonomov, an MP from Dupnitsa and one of the first to raise concerns about the deportations of Jews from Thrace and Vardar Macedonia, and Ivan Petrov, an MP who fought fierce battles in the National Assembly against the Law for the Protection of the Nation. Petar Mihalev, an MP from Kyustendil and one of the three members of the Kyustendil delegation, who left for Sofia on March 8, 1943 to stand up for the local Jewish community, received a life sentence.

Yad Vashem, Israel’s official Holocaust memorial, awards the honorary title of “righteous of the nations of the world” to non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews. As of April 2016, this title was awarded to 20 people from Bulgaria. The number of titles awarded is not necessarily an indication of the actual number of rescuers in a given country but reflects those cases that have been brought to the attention of Yad Vashem. Bulgaria was the only country under German influence or control in which the Jewish population actually increased during the war years, from 45,565 in 1934 to 49,172 in 1945.

Unfortunately, the fate of the Jews of Thrace and Vardar Macedonia was different. In March 1943, the Bulgarian authorities deported the Jews from the Bulgarian-ruled territories during the war. 11,343 people of Jewish origin who did not receive Bulgarian citizenship (unlike other nationalities in these territories) when they came under Bulgarian rule in 1941 were deported to Treblinka, where almost all were killed (12 of the deportees survived).

After the occupation of Greece and Yugoslavia by German troops, as an allied gratitude for the use of Bulgarian territory as a springboard for attacks on these countries, Germany in April 1941 transferred Yugoslav Macedonia and Greek Thrace to Bulgaria. About 8,000 Jews lived in Vardar Macedonia, and about 6,000 Jews in Thrace. These Jews, in agreement with the Germans, were deported by the Bulgarian authorities in 1943 to the death camps. The deportation was organised by the Minister of Internal Affairs of Bulgaria, Petar Gabrovsky, and the head of the Jewish Affairs Committee, Alexander Belev. On March 4, 1943, over 4,000 Thracian Jews were arrested and sent to transit camps until March 18-19, 1943. Then they were taken to Auschwitz. On March 11, 1943, Macedonian Jews were arrested and sent to a transit camp in Skopje. Eleven days later, 165 of the detainees, mostly doctors, pharmacists and foreigners, were released. The rest were deported to Treblinka. 11,343 Jews from North Macedonia and Thrace perished in the death camps.

After the war Bogdan Filov, Petar Gabrovsky and Alexander Belev, responsible for the persecution of Bulgarian Jews, after the war were accused of high treason and sentenced to death. Filov and Gabrovsky were executed on February 1, 1945. Belev was sentenced in absentia, then arrested and committed suicide.

In an article for DW (11.03.2018) on “How the Bulgarian Jews were saved” the head of the State Archives Agency, Mihail Gruev, says that despite the past 75 years, the intensive discussion of the facts continues both among the Bulgarian public and among the diasporas of Bulgarian Jews in Bulgaria and Israel. “The three factors for the salvation of the Jews – the majority in the National Assembly, the Church and the King – must be considered separately. Because each of these factors came from its own position. We cannot talk about a “pro-fascist” parliamentary majority at all, because there has never been a ruling fascist party in Bulgaria, much less a fascist party that has merged with the state. In my opinion, the pro-government majority was quite impersonal and quite inert. In this sense, the question remains unclear why this impersonal majority leaves one of the brightest traces in the history of Bulgaria and the world – the rescue of Jews with Bulgarian citizenship“, said Gruev.

In his “The Fragility of Goodness: Why Bulgaria’s Jews Survived the Holocaust“ Tzvetan Todorov says that “With the exception of Denmark, Bulgaria was the only country allied with Nazi Germany that did not annihilate or turn over its Jewish population.”,“The Bulgaria that emerges is not a heroic country dramatically different from those countries where Jews did perish. Todorov does find heroes, especially parliament deputy Dimitar Peshev, certain writers and clergy, and–most inspiring–public opinion. Yet he is forced to conclude that the “good” triumphed to the extent that it did because of a tenuous chain of events. Any break in that chain–one intellectual who didn’t speak up as forcefully, a different composition in Orthodox Church leadership, a misstep by a particular politician, a less wily king–would have undone all of the other efforts with disastrous results for almost 50,000 people.” and “Once evil is introduced into public view, it spreads easily, whereas goodness is temporary, difficult, rare, and fragile. And yet possible.”

My great-grandmother was one of the saved Bulgarian Jews during the Holocaust. She got married to an ethnic Bulgarian and lived happily with him in the Bulgarian town of Yambol. Her two brothers left for Mandatory Palestine and settled in Haifa.

My soul,

Is leafless…

And dreams,

Like criminals destroy the inner peace ..

My heart is leafless

Only the thoughts are covered with gold ..

It is in me ..

And I am in it ..

Jerusalem,

Even without touching you,

I am reaching out my soul ..

I draw an invisible bridge..

To you..

And I fly..

An invisible tear flows to the heart ..

Invisible, I am walking towards you now ..

I came ..

I’m not wearing anything

Except for a soul ..

Nefesh Yehudia…

Slaveya Nedelcheva, 07.06.2013 (the poem was originally written in Bulgarian)

This article was originally published in Balkans in-site on February 8, 2022.

References

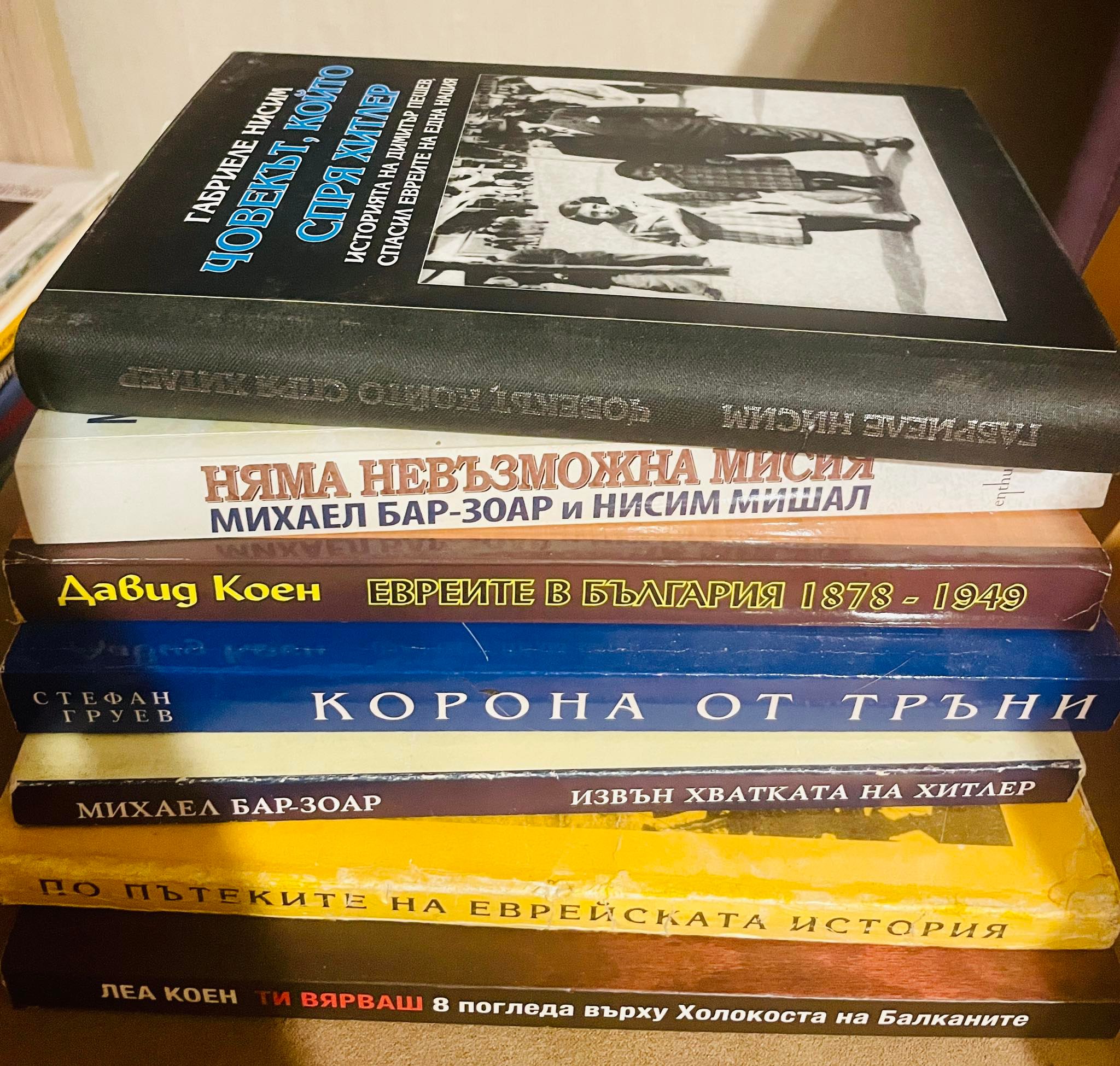

- Gabriele Nissim. The man who stopped Hitler, 1999

- David Cohen. Jews in Bulgaria 1878-1949, 2008

- Stefan Gruev. Crown of thorns, 2009

- Michael Bar Zohar. Beyond Hitler’s Grasp. The Heroic Rescue of Bulgaria’s Jews, 1998

- Lea Cohen. You believe : eight views on the Holocaust in the Balkans, 2012

- https://www.dw.com/bg/%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%BA-%D0%B1%D1%8F%D1%85%D0%B0-%D1%81%D0%BF%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8-%D0%B1%D1%8A%D0%BB%D0%B3%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B5-%D0%B5%D0%B2%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B8/a-42927519

- http://archaeologyinbulgaria.com/2016/03/10/bulgaria-celebrates-73rd-anniversary-since-rescue-of-bulgarian-jews-from-holocaust-of-nazi-death-camps

- https://shalom.bg/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Holocoust-ENG.pdf

- Tzvetan Todorov. “The Fragility of Goodness: Why Bulgaria’s Jews Survived the Holocaust“, 2001

- Haim Oliver. We Were Saved: How the Jews in Bulgaria Were Kept from the Death Camps, 1978

- Christo Boyadjieff. Saving the Bulgarian Jews, 1989